Two Suicides And The Inconsistent Cultural Application of Self-Autonomy

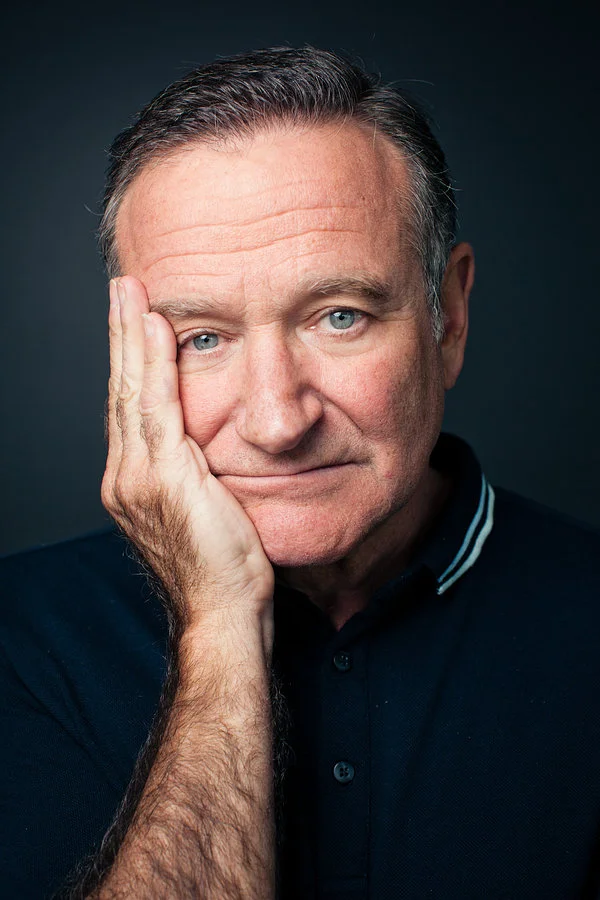

Robin Williams’ decision to end his life on August 11, 2014, was universally labeled “tragic.” This was a death that should have been prevented, we were told. And who could argue the point? Robin was adored, so much so that our collective pain demanded a scapegoat on which to pin the blame. Several were offered: dementia, addiction, Parkinson’s Disease, depression and a waning acting career, to name a few.

Curiously, however, when relatively unknown 29-year-old Brittany Maynard who was suffering from terminal brain cancer announced her decision to end her life - but legally in the state of Oregon – it was described as “strength and bravery” and celebrated as “heroic.” Hers was a not a death to be prevented, but one to be embraced by enlightened people everywhere, we were lectured. And so on November 1, 2014, unlike the pitiable Robin, Brittany died with “dignity.”

One has to wonder, why the double standard? After all, Robin and Brittany both chose to end their suffering by ending their lives, and for personal reasons they deemed sufficient. Yet Robin’s decision was judged regrettable whereas Brittany’s was extolled with evangelistic fervor. Prior to Brittany’s suicide she produced a short video inviting others to “Join her movement” by giving financially so “death with dignity” laws might be enacted, allowing others to receive assistance in their suicides, too. Yet imagining a similar video where Robin invites us to join his movement prior to hanging himself with a belt is repulsive. Such an obscene campaign would most certainly not enjoy the admiration Brittany’s did.

Perhaps the court of public opinion judged these suicides differently because it was believed Robin’s problem(s) could have been “fixed.” Maybe with the right drug, the right therapy, or if CBS had not cancelled his TV series, The Crazy Ones, Robin could have reclaimed his happiness and “seized the day” once again. Brittany’s circumstances on the other hand, appeared hopeless. After all, if brain cancer is not grounds for justifiable suicide, what is?

Maybe the difference is found in the manner in which these two died. Hanging oneself from a doorframe is crude and unrefined and evokes unpleasant images. It makes us uncomfortable. However, drugs prescribed by a physician (lethal though they may be) provide a degree of respectability. Let’s face it, taking your ailing dog to the vet to be “put down” is understandable; taking him out behind the barn with a shotgun seems barbaric. If this sounds cynical consider the Los Angeles Times opinion piece by Andrew Klavan (August 19, 2014) which typified the public response to Willliams’ death: “Robin Williams once made me laugh so hard I literally fell off the sofa in my TV room. It is deeply unpleasant to picture him dying the way he did.”

Here’s a possibility: Williams’ death offended us because he dared to go quietly, denying us the chance to press our noses against his bathroom window. Brittany Maynard, on the other hand, had the decency to broadcast her decision to the world inviting us in for a peek and sparking media frenzy. Although no crowd egged her on to jump from her “ledge,” the voyeuristic camera crews waited with baited breath for the news they’d surely profit from--that Brittany courageously carried through with her promise.

To press the cynicism, what if the real difference in how people viewed these suicides is merely one of utility? Robin, the comedic genius, made us laugh, whereas Brittany contributed nothing measurable to our lives. We need comedians, but anonymous people are expendable.

Our society wants to have their cake and eat it too. They want to don their black robes and with gavel in hand judge one person’s suicide tragic while ruling another’s courageous. But if personal autonomy, which now delivers the moral and legal justification for nearly every vice or vulgarity reigns supreme who are we to judge the reasons for which people choose to kill themselves? Suppose Robin’s suicide was influenced, as many have suggested, by depression, addiction or a fading career. So what? If taking one’s own life can be viewed as morally heroic under certain circumstances, shouldn’t it always be viewed as morally heroic under every circumstance? In a world where personal happiness trumps all other ethical considerations, who are we to sit in judgment when one concludes his comfort or happiness has been irreversibly lost? If physical suffering can provide legitimate moral shelter for suicide, why can’t emotional or psychological suffering? If we respect Brittany’s reasons for killing herself doesn’t our commitment to the new “tolerance” obligate us to respect Robin’s as well?

If not, maybe the enlightened ones will be so kind as to report to us unthinking, non-feeling Neanderthals which suicidal deaths we should mourn and which ones we should view as valiant and brave.

In a world where personal autonomy is deified one supposes he is morally free to take his own life. However, this kind of world cannot accommodate moral judgments over the reasons for which or the manner in which people choose to end their lives. Regardless of their respective reasons, Robin's and Brittany’s decisions to end their lives were both admirable, or they were both lamentable. Celebrating Brittany’s decision to commit suicide obligates us to stop pitying Robin and to embrace his decision as well. We simply cannot have it both ways.